"Under current conditions, it is impossible to end the war. It is a disgrace."

Prehistory

Despite the loss of Port Arthur, the destruction of the Pacific fleet, and setbacks in the Manchurian theater, Russia did not lose the war (Mukden; Tsushima tragedy). The land army grew stronger and was able to go on the counteroffensive, driving the enemy back to the sea and reclaiming positions in Manchuria and Korea.

The Japanese Empire was utterly exhausted and could not continue fighting. They faced financial ruin and a depleted military. More than half of Japan's budget went towards the war, and they found themselves unable to sustain further conflict. The Japanese leadership sought to explore the possibility of a peace agreement through European and American intermediaries.

In terms of military and economic strength, Russia was vastly superior to Japan and could have continued the war. However, the significant losses at the front, the tragic defeat of the fleet, unrest at home, and pressure from the international community compelled St. Petersburg to accept a peace agreement unfavorable to Russia.

When comparing the military and financial capabilities of Russia and Japan, it is clear that had the war persisted, Japan would have faced defeat. The Japanese command recognized that their army was nearing a breaking point, and any new confrontation could lead to a decisive loss. Thus, Japanese generals pushed the government to secure peace while the situation still favored them.

It is not surprising that just three days after the victory in the Tsushima Strait, Japanese Foreign Minister Yutaro Komura instructed the Japanese ambassador in Washington to inquire if President Roosevelt would consider a mediation role. On May 23 (June 5), Roosevelt instructed the U.S. ambassador to Russia, George Meyer, to secure a meeting with Emperor Nicholas II and "try to convince him that continuing the war was utterly futile and could result in the loss of all of Russia's possessions in the Far East."

The Great Game

Initially, both England and the United States supported Japan, pitting it against China and later against Russia. The leaders of the Anglo-Saxon world viewed Russian civilization as the primary adversary in the Great Game, which aimed at controlling global affairs. They preferred to avoid direct confrontations with a strong opponent, opting instead to manipulate others into fighting for them. Historically, Britain had set Russia against Sweden, Turkey, and France. In 1904, it orchestrated Japan's conflict with Russia, later managing to incite Germany against Russia, the two strongest rivals of the Anglo-Saxons in Europe.

The Japanese Empire could not have waged war without the military, material, and financial backing of British and American capital. Before the war, the British had financed Japan and helped train its military, essentially building a first-class navy for the nation.

When the war commenced, in April 1904, banker Jacob Schiff and the large financial house Kuhn, Loeb and Company, along with a syndicate of British banks, provided Tokyo with a loan of $50 million at a steep interest rate (6% per annum); half of the loan was placed in England, and half in the U.S.

In November 1904, another loan was issued for $60 million in England and the U.S. (also at 6% per annum). In March 1905, a third Anglo-American loan of $150 million (4.5%) followed. By July 1905, Japan received a fourth loan of $150 million (4.5%). This influx of funds allowed Japan to cover over 40% of its war expenses, which reached 1.73 billion yen and continued to escalate.

The U.K. and U.S. effectively backed Japan, investing their resources to enable Japan to confront Russia. The Japanese served as "cannon fodder" for the Anglo-Saxons during this conflict. Without British and American financial support, Japan could not have sustained the war for long.

Japan was ultimately drained from the war, having spent about 2 billion yen, and saw its national debt swell from 600 million yen to 2.4 billion. Annual interest payments on loans became a staggering 110 million yen.

Conversely, Russia experienced little economic or financial strain from the war. The harvest of 1904 was bountiful, and industrial growth continued that year. Tax collections proceeded as in peacetime, and the gold reserves of the State Bank grew by 150 million rubles in 1904.

Russia's military expenditures for the first year of war, around 600 million rubles, were partially covered by surplus treasury funds (budget balances from previous years) and partly through foreign loans. Subscriptions for two loans exceeded the amounts needed multiple times. In May 1904, a loan of 300 million rubles was secured from France, followed by a 232 million ruble loan from Germany at the end of 1904. Thus, in continental Europe, Russia had a solid backer; both France and Germany were supportive of Russia, allowing it to continue its fight in the Far East with relative ease.

France was an official ally of Russia, while the Germans preferred a situation where Russia was mired in the Far East, reducing its interference in European affairs. German Kaiser Wilhelm II even began to refer to Nicholas II as the "Admiral of the Pacific Ocean," effectively proposing an alliance with Russia. Unfortunately, the advocates of the Entente and Western influences derailed this potential alliance, resulting in the Russians and Germans, who had no fundamental differences at the time, being turned against each other, much to the benefit of Britain and the U.S.

Following the Hull incident in October 1904, the British government issued threats against Russia. Berlin promptly backed St. Petersburg. On October 27, Kaiser Wilhelm II personally telegraphed Emperor Nicholas II, informing him that Britain intended to prevent Germany from supplying coal to the Russian navy. Wilhelm proposed to form a "powerful alliance" against Britain and jointly compel France to join Russia and Germany in a united front.

Russian Foreign Minister Lamsdorf, who was pro-French, opposed this course of action. Tsar Nicholas II responded: "I favor an agreement with Germany and France. We must rid Europe of Britain's insolence." On October 16, he telegraphed Kaiser Wilhelm: "Germany, Russia, and France must unite. Please draft such a treaty. Once we accept it, France must align with her ally. This concept has often occurred to me." This alliance could have spared Europe from the large-scale war that the Anglo-Saxons were preparing.

In Berlin, a draft alliance treaty was quickly formulated. It stipulated that "in the event one of the two empires is attacked by a European power, its ally will come to its aid with all its land and sea forces." If necessary, both allies would act in unison to remind France of its obligations under the Franco-Russian alliance treaty.

Implementing this initiative would have resulted in an anti-British continental coalition in Europe, led by Germany and Russia with France’s participation, or it would have jeopardized the Franco-Russian alliance, which was already detrimental to Russia, making Russians "cannon fodder" under England and France’s manipulation.

Unfortunately, St. Petersburg was never able to escape this predicament. Influential agents from England and France in Russia managed to persuade Nicholas II to abandon the alliance with Germany. Consequently, both the Russians and Germans became "cannon fodder," leading to the devastation and plunder of their empires.

This situation was further complicated by the Moroccan Crisis (March 1905 to May 1906), a dispute between France and Germany over control of Morocco that almost led to war between the two countries.

In light of these circumstances, Russia had a relatively secure position in Europe, as both France and Germany had an interest in its stability. This allowed Russia to continue its efforts in the Far East.

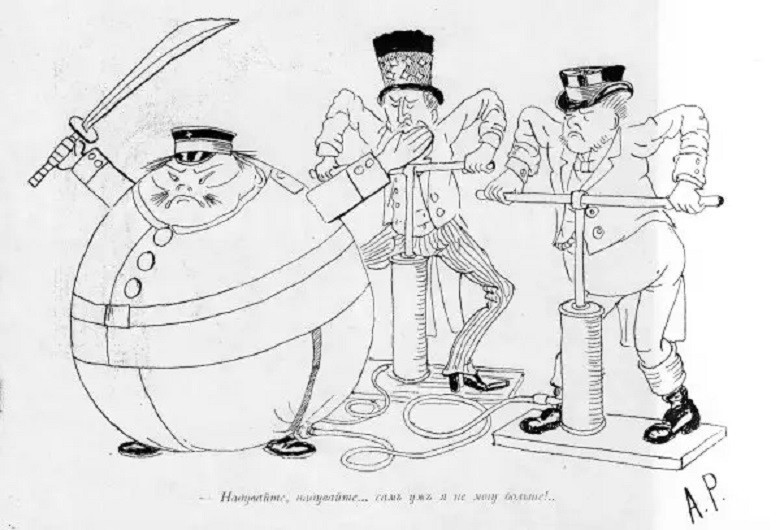

Many people already understood the provocative role of England and the USA at that time. In particular, the press regularly published corresponding cartoons. A. A. Radakov's cartoon in the magazine "Shut" "Inflate, inflate... I can't do it myself anymore!" The author's irony is obvious: the word "naduvat" has several meanings in Russian. In addition to the main one - "to fill with air", it is used in the sense of "to deceive".

Many people already understood the provocative role of England and the USA at that time. In particular, the press regularly published corresponding cartoons. A. A. Radakov's cartoon in the magazine "Shut" "Inflate, inflate... I can't do it myself anymore!" The author's irony is obvious: the word "naduvat" has several meanings in Russian. In addition to the main one - "to fill with air", it is used in the sense of "to deceive".

Peace Talks

Recognizing that Japan could no longer sustain its efforts and would face further defeat, the English and American powers opted to consolidate their gains. With relations with Russia soured, the British could not propose to mediate peace talks. Thus, the Americans stepped in.

Initially, the American government and press welcomed Japan's early successes in the war. However, as events progressed, Washington grew concerned. The Americans did not desire either Russia’s total defeat, which could enable Japan to strengthen its position in the Pacific and in China—where America had its own interests—or Japan’s possible loss.

In March 1904, as the war began, American President Theodore Roosevelt candidly conveyed to the German ambassador that the U.S. was interested in seeing both Russia and Japan "trouble each other as much as possible" and that post-peace, regions of friction should remain to create geographical tensions to maintain readiness and moderate their ambitions elsewhere. He believed that this would prevent Japan from threatening Germany in Jiaozhou and the U.S. in the Philippines.

The Russian leadership, however, lacked the resolve to continue the conflict. Following the defeat at Tsushima and the emergence of revolutionary events in Russia, there was a growing consensus that peace was necessary.

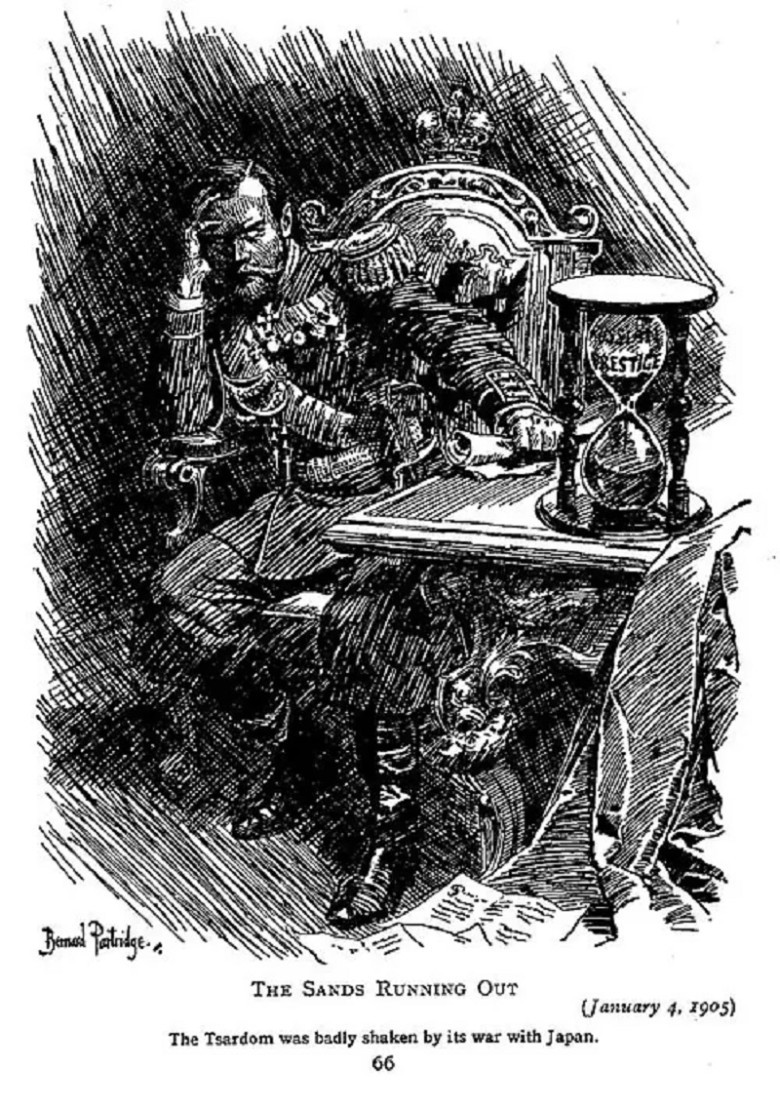

On May 24 (June 6), 1905, a military conference presided over by Nicholas II was convened at Tsarskoye Selo to discuss the need for peace. Views were sharply divided. War Minister General Sakharov contended that "under the current conditions, it is impossible to end the war. Given our total defeat, with no victories or even successful initiatives, this is disgraceful. It would lower Russia’s prestige and remove it from the ranks of the great powers for a long time. We must continue the war not for material gains, but to remove the tarnish that would remain if we have no success, as we have experienced thus far."

General Sakharov was supported by state controller Pavel Lobko, who noted that peace would worsen domestic conditions by bringing back an army that had suffered defeat without reward. Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, however, advocated for negotiations.

On May 25, 1905, American Ambassador Meyer urgently requested an audience with the Tsar, emphasizing the necessity of concluding peace without delay. As was typical, the Tsar remained silent during the discourse.

Ultimately, Nicholas agreed to pursue negotiations. On June 29, Sergei Witte, Chairman of the Committee of Ministers, was appointed the chief commissioner for peace negotiations with Japan. Nicholas instructed Witte to seek peace but not at any cost, demanding no territorial concessions or indemnities to Japan.

On July 29 (August 9), a peace conference convened in Portsmouth, a resort town on the Atlantic coast of the U.S. The Japanese delegation was led by Baron Yutaro Komura, with Kogoro Takahira serving as his main aide.

On July 30 (August 10), following the formalities of exchanging credentials and introductory statements, Komura presented Witte with a note containing twelve demands. Japan insisted on the annexation of Sakhalin and adjacent islands, compensation for military expenses (indemnity), limits on Russian naval forces in the Far East, and the surrender of all Russian ships interned in neutral ports. Moreover, Japan demanded a free hand in Korea, the complete evacuation of Russian troops from Manchuria, and the transfer of lease rights for the Liaodong Peninsula along with Port Arthur and Dalny, in addition to ceding the entire railway between Port Arthur and Harbin along with the coal mines.

Tokyo was amenable to Russia retaining the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) but only with restricted rights for economic use. Japan sought unlimited fishing rights along the Russian coastline in the Sea of Japan, the Sea of Okhotsk, and the Bering Sea, as well as associated rivers and bays.

The most contentious issues revolved around the payments and ownership of Sakhalin. While Tsar Nicholas II was firm against territorial concessions and outright payments, Witte, being more flexible, proposed options for either financial compensation or territorial cessions. The Japanese sought both, demanding an exorbitant sum of 1.2 billion yen.

As the negotiations dragged on, the Japanese military leadership became increasingly anxious. The tension arose from a fear of renewed hostilities, which could lead to catastrophic defeat. Japanese researcher Shumpei Okamoto noted that "Commander-in-Chief of the Manchurian Army Komada, frustrated with the slow progress in negotiations, urged his government to finalize a peace agreement and avoid the risk of resuming fighting." The military was keenly aware that their forces could not withstand another campaign against Russia.

On August 28 (new style), a joint meeting of the genro (an informal council under the emperor), the government, and senior military officials took place, attended by Emperor Mutsuhito. Finance Minister Sone reported that war was untenable as the Japanese Empire could not find additional financing sources. Consequently, the outcome of the meeting was a directive to Komura to reach an agreement rapidly, even if it meant relinquishing demands for monetary compensation and territorial changes.

At a moment when the Japanese leadership was poised to relinquish its main demands for territorial concessions, the Americans intervened once more. Roosevelt sent a telegram to the Russian Tsar, applying pressure and expressing confidence in Japan's insurmountable claims. He warned that continued warfare could result in the loss of all Russian territory east of Lake Baikal, threatening Russia's status as a Pacific power.

Simultaneously, American Ambassador Meyer began persuading Nicholas II to make concessions, promising U.S. mediation to persuade Japan to forgo its compensation demands. Lacking diplomatic savvy, Nicholas II remained largely reticent, but eventually "mentioned in passing" that Russia might contemplate the possibility of ceding South Sakhalin. This comment swiftly reached Washington and then Tokyo, prompting Japan to persist in demanding territorial gains.

Ultimately, Russia ceded the southern part of Sakhalin to Japan along the 50th parallel. Witte could only dismiss the demand for surrendering all Russian ships interned in Chinese, Indonesian, and Philippine ports. The issue of indemnity also remained unresolved, with Russia eventually paying 46 million rubles in gold for the upkeep of Russian prisoners in Japan.

On August 23 (September 5), 1905, the Portsmouth Peace Treaty was signed. The treaty declared peace and friendship between the emperors of Russia and Japan, as well as between their nations and subjects.

According to the treaty, Russia recognized Korea as under Japanese influence, surrendered leasing rights to the Liaodong Peninsula along with Port Arthur and Dalny, and granted parts of the South Manchurian Railway from Port Arthur to Kuanchengzi. Additionally, the treaty stipulated the conclusion of a convention on fishing along the Russian coasts of the Sea of Japan, Sea of Okhotsk, and Bering Sea, securing only the commercial use of Manchurian railways for both parties.

Russia ceded to Japan the southern territory of Sakhalin (from the 50th parallel), along with "all adjacent islands." The two nations also agreed to exchange prisoners of war.

Moreover, China bore the burden of Russia's defeat in the war. The Qing government was compelled to accept all terms of the Treaty of Portsmouth, including the lease transfer for the Liaodong Peninsula with Port Arthur and the South Manchurian Railway to Japan. China also granted Japan permission to construct a railway from the mouth of the Yalu River to Mukden, along with pledges to open 16 cities in Manchuria for international (i.e., Japanese) trade, including Jilin, Harbin, Hailar, and Ainun.

Portsmouth negotiations. Russian delegation (far side of the table) - Korostovets, Nabokov, Witte, Rosen and Planson; and Japanese (near side of the table) - Adachi, Ochiai, Komura, Takahira and Sato

Portsmouth negotiations. Russian delegation (far side of the table) - Korostovets, Nabokov, Witte, Rosen and Planson; and Japanese (near side of the table) - Adachi, Ochiai, Komura, Takahira and Sato

Significance

Russia suffered a significant strategic defeat, losing substantial ground in the Far East. This weakened state allowed Japan to build upon its success, paving the way for subsequent Japanese expansion until Russia sought historical retribution in August 1945 (the Manchurian Blitzkrieg by the Soviet Army).

The plans of Britain and the United States to engineer a conflict between Russia and Japan and thereby weaken Russia were realized. Both Russia and Japan were dissatisfied with the war's outcomes, fostering lingering hostility that benefited England and the U.S.

The "rehearsal" for the First World War proved effective, exposing Russia’s vulnerabilities.

Most Russians regarded the war's outcome and the Treaty of Portsmouth as a humiliation. It was not without reason that Joseph Stalin, a prominent figure in Russian civilization and the Russian superethnos, later reflected on this event. He understood the urgency in restoring Russia's standing in the Far East (including Southern Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, and Port Arthur).

The Japanese Empire suffered about 135 casualties due to deaths or wounds and illnesses during the conflict, with approximately 554 cases requiring medical attention.

In contrast, Russia's total losses amounted to around 400 individuals, including those killed, wounded, missing, or evacuated due to illness. The financial toll on Russia reached 2.347 billion rubles, in addition to approximately 500 million rubles for railroads, ports, and the sunk vessels, both military and commercial, that were handed over to Japan.

Key factors contributing to Russia's defeat included: 1) Petersburg's indifference to military and economic development in the Far East; 2) a lack of will among military and political leaders in prosecuting the war; 3) the decline of the Russian military elite, with top posts filled by mediocre careerists and opportunists, as well as individuals ill-suited for wartime command; 4) financial, military, and political support from England and the U.S. towards Japan; 5) the geographical distance of the Manchurian front from Russia's European heartland, where the majority of the empire's military and economic resources were located.

Few were held accountable for the failures of Russian generals and admirals. Witte, who effectively acted as an agent of Western influence and played a significant role in instigating Russia's conflict with Japan, was elevated to the title of count by Nicholas II, earning him the sarcastic nickname "Count Polusakhalinsky."

General Admiral Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, responsible for inadequately preparing Russia's armed forces in the Far East, was allowed to retire with the rank of General Admiral and went to Paris for a "well-deserved rest," popular among the Russian elite at that time. His competitor, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, who was implicated in the fleet's mismanagement and the financial misadventures in Manchuria, also headed to the Cote d'Azur for an extended retreat.

Legal action was primarily directed towards: Lieutenant General Stessel, head of the Kwantung fortified region; Lieutenant General Smirnov, commandant of the Port Arthur fortress; Lieutenant General Fok, head of ground defense; Major General Reis, the chief of staff for the Kwantung fortified region; Vice Admiral Stark; and Rear Admirals Loshinsky, Grigorovich, and Viren.

The Supreme Military Criminal Court delivered its verdict: Lieutenant General Stessel was sentenced to execution by firing squad, while Lieutenant General Fok received a reprimand. The court acquitted Smirnov and Reis, and all other charges were dismissed. Tsar Nicholas II subsequently commuted Stessel's sentence to ten years in a fortress, but Stessel only served about a year in Peter and Paul Fortress before being released.

A similar outcome befall the "heroes" of the Battle of Tsushima. Admiral Rozhestvensky was exonerated by the naval court after being severely injured in battle. The court found Rear Admiral Nebogatov and three ship commanders guilty of the criminal surrender of ships and sentenced them to death by firing squad. However, the Tsar commuted their death sentences to ten years in a fortress as well, and they were soon released after serving only a few months.

This situation exemplified a systemic crisis not only of the civilization and the Romanov project but also of the state itself, leading ultimately to catastrophe.

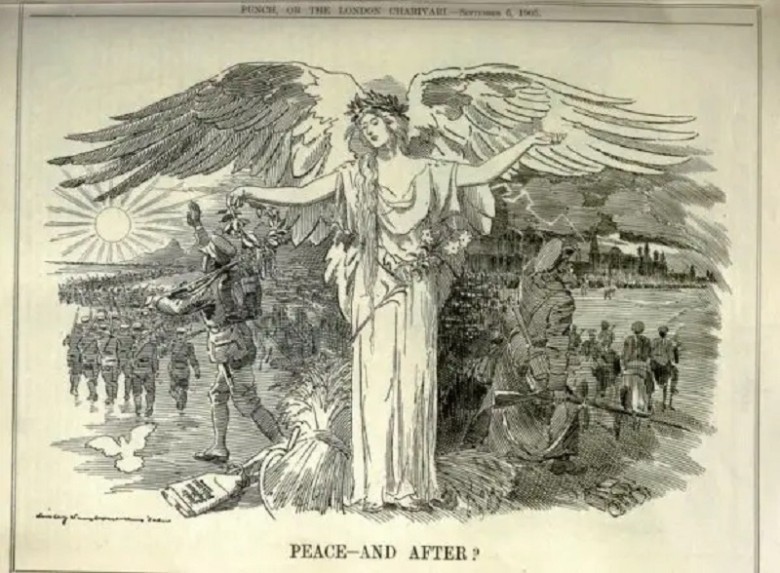

The day after the peace was concluded, Punch published a cartoon with the significant title "Peace - and then?", in which the author's position was clearly visible. The wings of the angel of peace were spread over the soldiers of both armies leaving their positions. But above the head of the Japanese soldier, a laurel wreath of victory was visible, and at his feet, an oar with the inscription "Anglo-Japanese Alliance". And while the Japanese, followed by a white dove, moved towards the rising sun, the Russians were leaving into a thunderstorm.

The day after the peace was concluded, Punch published a cartoon with the significant title "Peace - and then?", in which the author's position was clearly visible. The wings of the angel of peace were spread over the soldiers of both armies leaving their positions. But above the head of the Japanese soldier, a laurel wreath of victory was visible, and at his feet, an oar with the inscription "Anglo-Japanese Alliance". And while the Japanese, followed by a white dove, moved towards the rising sun, the Russians were leaving into a thunderstorm.

Photo source: Wikipedia.org

Comments

0 comment